https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?search=bugle&title=Special:MediaSearch&go=Go&type=image

I was doing some work recently on a Victorian newspaper with an undeniably laudable social purpose. It was called the Fonetic Nuz (Phonetic News) and appeared in January 1849. It was the brainchild of one Alexander Ellis – a polymath who, having graduated in Classics and Mathematics from the University of Cambridge, was enabled by a family bequest to devote his life to his own educational interests.

Holidaying in Italy, the young Ellis became fascinated with the sound of spoken Italian, which he sought to render orthographically. This led him to an interest in phonetics more generally. He was for some time associated with Isaac Pitman – best-known today as the originator of the system of shorthand that became an essential skill of stenographers and secretarial staff in the days before technology made both recording and text production widespread. (My mother was a trained shorthand typist, so it’s only a generation or two back.)

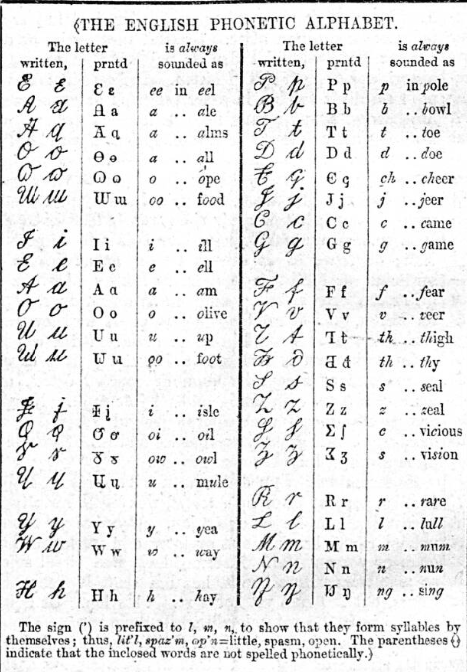

Ellis and Pitman shared a belief that English spelling – much of which has its origins in etymology rather than being remotely phonetic – presented a serious barrier to widespread literacy. They were advocates for not only spelling reform, but for an alphabet in which each phoneme was represented by one grapheme only. This naturally required rather more than twenty-six letters. Nevertheless, they both attempted, individually and jointly, to arrive at such a new alphabet. They achieved a consensus with the 1847 alphabet, which Ellis grandiosely entitled ‘The English Phonetic Alphabet’ in his newspaper, launched as a practical demonstration of the system.

Perhaps unsurprisingly, it didn’t catch on…comprising forty characters, many of which were unfamiliar to standard orthography (though phoneticians today will recognise some of them), Ellis’s claims that this alphabet would promote rapid literacy were rather too optimistic, however well-intentioned. The fact that he couldn’t resist an appendix that added several other symbols to represent sounds in ‘foreign’ words hints at the limitations of his proposed alphabet. Spelling reform saw some limited implementation in the United States but otherwise our gloriously, maddeningly eccentric language continues with what Ellis dismissed as ‘old school’ spelling. And maybe it was less of a barrier than he believed, given the spread of literacy from the later nineteenth-century.

A rather more successful and recent campaign to promote comprehension amongst the less-educated also involved a newspaper – and happened in the place I now call home, Liverpool. The Plain English campaign, which has sought to demystify the antiquated language that bedevils legal and official communications since 1979, is today very well-known and still makes awards of its Crystal Mark to recognise organisations that deploy plain English. More details are here: https://www.plainenglish.co.uk/ The campaign was founded by Chrissie Maher, a formidable woman who, despite having endured a tough upbringing with limited formal education was intelligent, driven, principled and unafraid to tackle the establishment.

What surprised me was finding that, at a local level, she had also been the driving force behind a community newspaper, the Tuebrook Bugle, which ran from 1971-79 (longer than the short-lived Victorian papers I’m researching.) Examples – and an overview of the paper – can be found here: https://www.freepressarchive.com/bugle/intro.html The professionalism demonstrated in both the form and content of the Bugle are impressive. Though they were able to call on help from staff at the Liverpool Daily Post and Echo in the beginning, the Bugle was proudly and democratically written ‘by the people, for the people’, to high editorial standards. Of course its focus is local – but it was nonetheless a real newspaper. Perhaps it was the success of this publication that convinced Chrissie that good, plain standard English should be the default language of official publications. I’d like to think that Alexander Ellis might have approved of literate, articulate ‘ordinary’ people acting to reform the archaic language of the legal and political establishment.