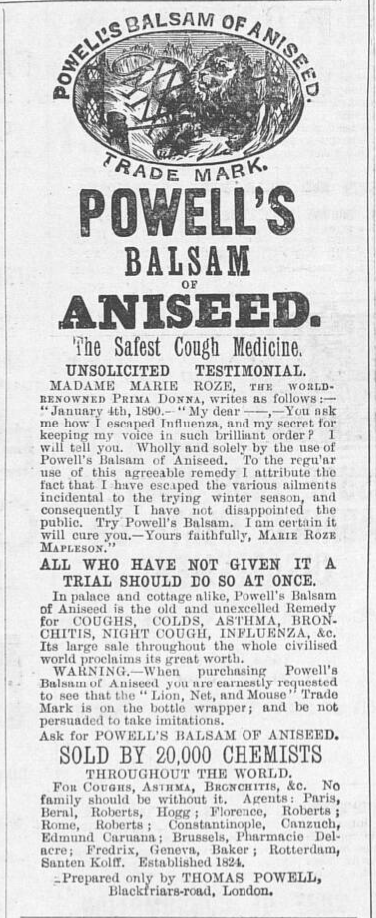

I’m currently suffering with my first cold of the year. It has hit me quite hard. I think one of the unfortunate consequences of the necessary arrangements made during the Covid-19 pandemic is that many including me, by acting to avoid spreading Covid, avoided other regular viruses. So, my system is less prepared and working harder to fight it off. At times like this, wouldn’t it be great if there was indeed an amazing catch-all remedy like Powell’s Balsam, bound to cure anyone whether in ‘palace or cottage’. But then newspapers and quack remedies – and advertisements for them – have often featured together.

One example of those arose in some recent research I did on the mid-nineteenth-century illustrated press, for which the starting point is, of course, the Illustrated London News whose founder, Herbert Ingram, was only able to take the considerable risk of launching his new paper in 1842 having made a fortune from taking out what we would today call a franchise on a quack medicine he marketed as ‘Parrs Life Pills’. These were essentially a herbal laxative but his promotional material linked them with the myth of a very long-lived countryman (Old Parr) from Shropshire who was supposedly merrily fathering children into extreme old age!

Ingram was in many ways an archetypal figure of the Victorian age – from an artisanal background, he partnered a flexible relationship with truth with ruthless drive and ambition, eventually achieving solid middle-class respectability as a member of parliament and landowner, with a statue erected to him by the grateful citizens of Boston in Lincolnshire whom he represented. Yet there was a dark side to his character which only emerged in public decades later and, despite having been presented in a biographical account written by Isabel Bailey at least twenty years ago, remains largely overlooked. (see for example, her entry in the ODNB, https://doi.org/10.1093/ref:odnb/14416).

Not only did Ingram manage to fall out with and break away acrimoniously from almost every business partner who helped to launch his dream project of the illustrated newspaper, he also reneged at the last minute on an agreement to sell it that he had made with another printer and publisher, John Tallis – who launched a rival paper instead, the Illustrated News of the World (no relation to the title that was involved in mobile phone hacking a few years ago). Ingram was, it turns out, also something of a sexual predator, molesting his own sister-in-law on two separate occasions, both times when she was laid up in bed with a cold. This was, in the way of ‘respectable’ people of the time, dealt with privately and quietly, though Ingram always resented that he had been called to account for his actions at all. Tallis – of whom no such accusations ever appeared – struggled to establish his paper in the face of Ingram’s already well-known one. How different it might have been had the latter’s scandal become public!

The story of these two men is one I hope to tell in more detail – perhaps a project to look at when my PhD thesis is done. I’d need to trace the Tallis family line to see if his personal archive papers remain; in 1969 they were in possession of his grandson but after that, the trail rather goes cold. But, for me, their competition and their complementary personalities are emblematic of the age in which they lived and they are certainly part of the story of the development of the illustrated newspaper press in the second half of the nineteenth century. And it might never have happened in the way it did if not for a cure-all remedy for a common complaint.

With that, I’m off to take some decongestant…or maybe a hot toddy.

Information on image: extracted from the Illustrated Sporting and Dramatic News, 22/11/1890, p. 35

From the British Newspaper Archive: https://www.britishnewspaperarchive.co.uk/viewer/BL/0001857/18901122/064/0035?browse=true&fullscreen=true