One of my main arguments in researching short-lived nineteenth-century newspapers is that the periodical press was in a state of near-constant flux in the nineteenth century; it was only towards the end of the 1800s and into the 1900s that there was a degree of consolidation into familiar, established publications (and also clearer separation between ‘national’ newspapers and local ones). Right at the start, I wanted to try to measure the relative longevity of newspaper titles, to calculate the proportion of the periodical press that could be characterised as short-lived. All I would need to do, then, is to obtain an authoritative index of newspaper titles with their start and end dates, and undertake some data analysis. I soon found that no such single index exists; all we have are various catalogues and indexes, undertaken by many people for a variety of reasons. None is complete.

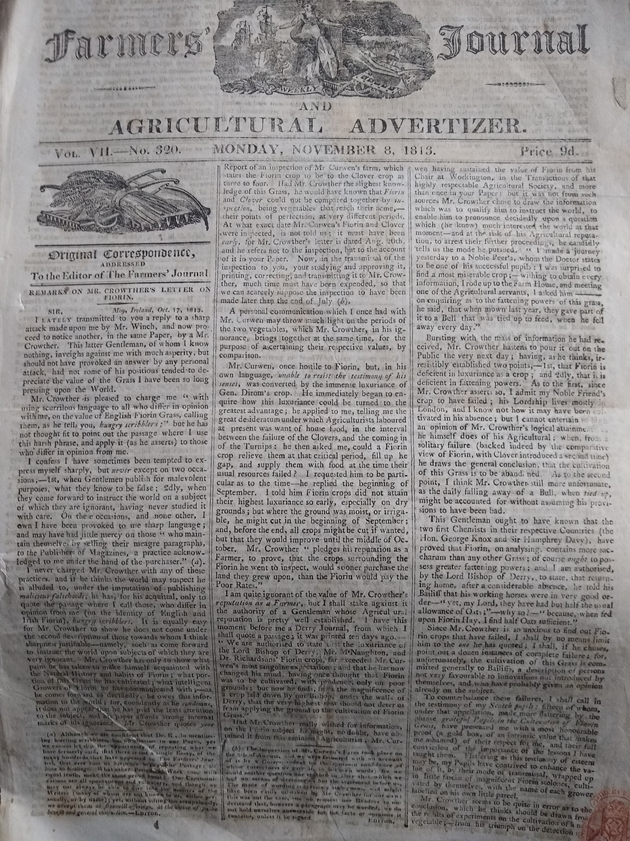

Deposit library holdings like those at the British Library do indeed contain many, many examples and are highly professionally curated; but this commitment to curation and preservation evolved over time and many newspaper titles came and went before there was systematic collection by the BL or its predecessor (for this purpose), the British Museum. Commercial catalogues such as Mitchell’s only really started in the mid-1840s and, despite grandiose claims to comprehensive coverage, clearly focussed on the most lucrative spaces for advertisers. What this means is that our knowledge of the newspapers of the early nineteenth century is especially patchy. The newspaper pictured here, for example, does not appear in the holdings of the British Library or earlier records from the British Museum (though the latter records a later Farmer’s Journal that ran from 1839 – 1846). Neither is it in the Waterloo Directory, though again similar titles are found both earlier and later. So, this rather expensive, quite specialist weekly journal, which must have been in print from some time in 1807 to judge from the issue number, though perhaps under different titles, is a mystery. As such, it’s an emblem, reminding me that so much about the nineteenth-century periodical press remains unknown.

I obtained it as a result of an act of generosity by an eminent scholar, Dr Andrew Hobbs, who was clearing out his office and decided to give away sundry treasures like this. I chose it, really, because I liked the masthead design. Alongside is a closeup of the graphic device. It juxtaposes Britannia ‘ruling the waves’ on the left, with a more clearly agricultural image on the right. But there’s so much going on in the image – the cultural connotations are incredibly rich; and all for what would be called a ‘logo’ today and something hardly noticed by regular buyers/readers.

I wonder why proprietors and printers, especially of non-illustrated publications, used these graphic devices on their mastheads. What were their motivations? To emphasise quality? To stand out? Merely as a printer’s flourish? Or to convey something at an almost subliminal level to current and potential readers? Just another little mystery to ponder. Interesting, though, that in our age of desk-top publishing and digital graphics, most newspaper mastheads today are so prosaic – this illustrated style is rather a lost art. Plus ça change…